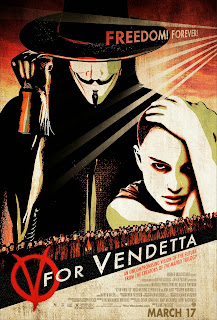

Part 7, in which we remember, remember the Fifth of November…

Still worn out from the back-to-back filming of the conclusion to their Matrix saga, the Wachowskis decided to take another step back for their next film project, this time acting only as writers and producers for their adaptation of Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s seminal V for Vendetta, and selecting their second-unit director on the Matrix films, James McTeigue, to step behind the lens for the actual shoot. The siblings had previously been drafted to pen the script by Joel Silver long before The Matrix, and decided to revisit the material as the post-9/11 political climate was eerily approaching Moore and Lloyd’s vision of a fascist dystopia.

Growing

up reading comics from the eighties/early nineties, I learned two things: 1.

The Prime Minister of the UK was a lady named Margaret Thatcher, and 2. British

comic book writers really didn’t like

her. In a way, we should be thankful for the Iron Lady’s rule, as it produced a

handful of comics that pushed the medium from “kid’s stuff” into more adult,

literate fare, of which V for Vendetta was

undoubtedly a member. Moore and Lloyd’s comic pushes all of that angst to its

most extreme conclusion, where the fierce Neo-conservatism of the West during

the reign of Thatcher and Reagan in the eighties led to full-out Nazism,

whereupon a lone vigilante takes it upon himself to wage an anarchist

revolution against the corrupt powers-that-be. The overall premise boils down

to “anarchy vs. fascism,” and while it may appear to be one way at first, the

comics are far more complex in their portrayals, what with the rather

humanistic qualities of the fascists and the completely cold and ruthless titular

anarchist.

And

that’s kind of where the filmmakers stumble in their intent. Make no mistake: V for Vendetta is a powerful movie, and

easily one of the best science fiction films from the last decade. But by

streamlining the original story and fitting it into a traditional, romantic

Hollywood narrative, the Wachowski’s rob the source material of its fitting

complexity. The British government come off as way too cartoonish, while the

terrorist freedom fighter V is perhaps a bit too cute and cuddly. This causes

considerable problems when V kidnaps Evey and puts her through a rather

harrowing recreation of his concentration camp experiences. In the comics it

works, because V is a remorseless bastard who cares for nothing but his

mission, but the filmic V is different. He wears an apron and makes breakfast

for Evey, he playfully fights a suit of armor while watching The Count of Monte Cristo… Hewing closer

to the romantic hero ideal, the filmic V becomes downright adorable. So

the fact that this character--one who the filmmakers have invested us in as a

tragic, Andrew Lloyd Weber-esque Phantom--ultimately kidnaps and tortures Evey

just to make a point is problematic to say the least, and speaks largely to the

question of artistic intent, with the message the filmmakers want to portray

sometimes being directly at odds with what the actual film is saying.

But, as problematic as that protracted section of the film is, it also contains the film’s best scene, and one of the most moving This is the “Valerie” section, where Evey finds a letter written by a woman across the hall who’s been black-bagged and imprisoned just for being a homosexual. It’s a scene that lays out the pointlessness and just-plain stupidity of bigotry so clearly that it’s hard to see how anyone watching it holding those views won’t at least consider questioning their beliefs after viewing it. Now I know assholes will always be assholes, and nothing short of a gun to the head will ever change the minds of brain-washed generations raised in a paternalistic, white society that has used the basic differences of people to subjugate and proliferate them into being a part of a system that sustains itself through class, us-and-them mentalities… but it’s nice to dream, and the scene remains effective, nonetheless.

The film is also extraordinarily well put together, in spite of the sometimes simplistic characterizations. The Wachowskis whittle down Moore and Lloyd’s epic tome of graphic literature into a 145 minute movie, and one that moves - without the benefit of resorting to cheap action every five minutes. It’s also edited together remarkably, with mirroring, rising and falling action that would trace the arc of a “V” itself. It’s a pretty stunning debut for James McTeigue… although it certainly feels more akin to the Wachowskis’ overall filmography. Of course, no movie is made on an island, and the “auteur” theory that tells us that each film has an author in its director doesn't quite fit the larger filmmaking process, but looking at McTeigue’s subsequent movies and here with V… well, two of those things are not like the other. I believe the Wachowskis definitely did the second-unit work here, and most likely completely directed the end fight all to themselves, but whatever the case, V for Vendetta continues their trend of thought-provoking ideas mixed in with popular entertainment, producing a rollicking good movie in the process.

No comments:

Post a Comment